Personal data has variably been called the new oil and gold of the digital era. While these comparisons are imperfect, data is without question the fuel that drives our connected and digitized world. Virtually every action a person takes online generates new data, of which the amount created is staggering, and continues to grow each year.

Which begs the question: what happens to all that data?

It may be as valuable as oil or gold to the companies that collect it, but consumers often have little understanding of, or control over, how their data is collected, stored, and shared. The more our digital footprints expand, the more uneasy people feel about the data collection practices of companies. This uneasiness is further justified by horror stories about sensitive data being hacked, sold, leaked, and otherwise abused.

In the United States, federal privacy laws mostly predate the Internet era and are insufficient to address the world of big data. Lacking a comprehensive data privacy regulation like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that protects Europeans, Americans are still very much living in the Wild West of data privacy.

But with growing concerns creating momentum for new privacy laws, more states are proposing solutions to tame the frontier. It’s looking more likely that a federal privacy law is in store for the U.S. as well.

In this article, we examine the history and current state of privacy laws in the U.S. before exploring current and future data protection laws state by state.

|

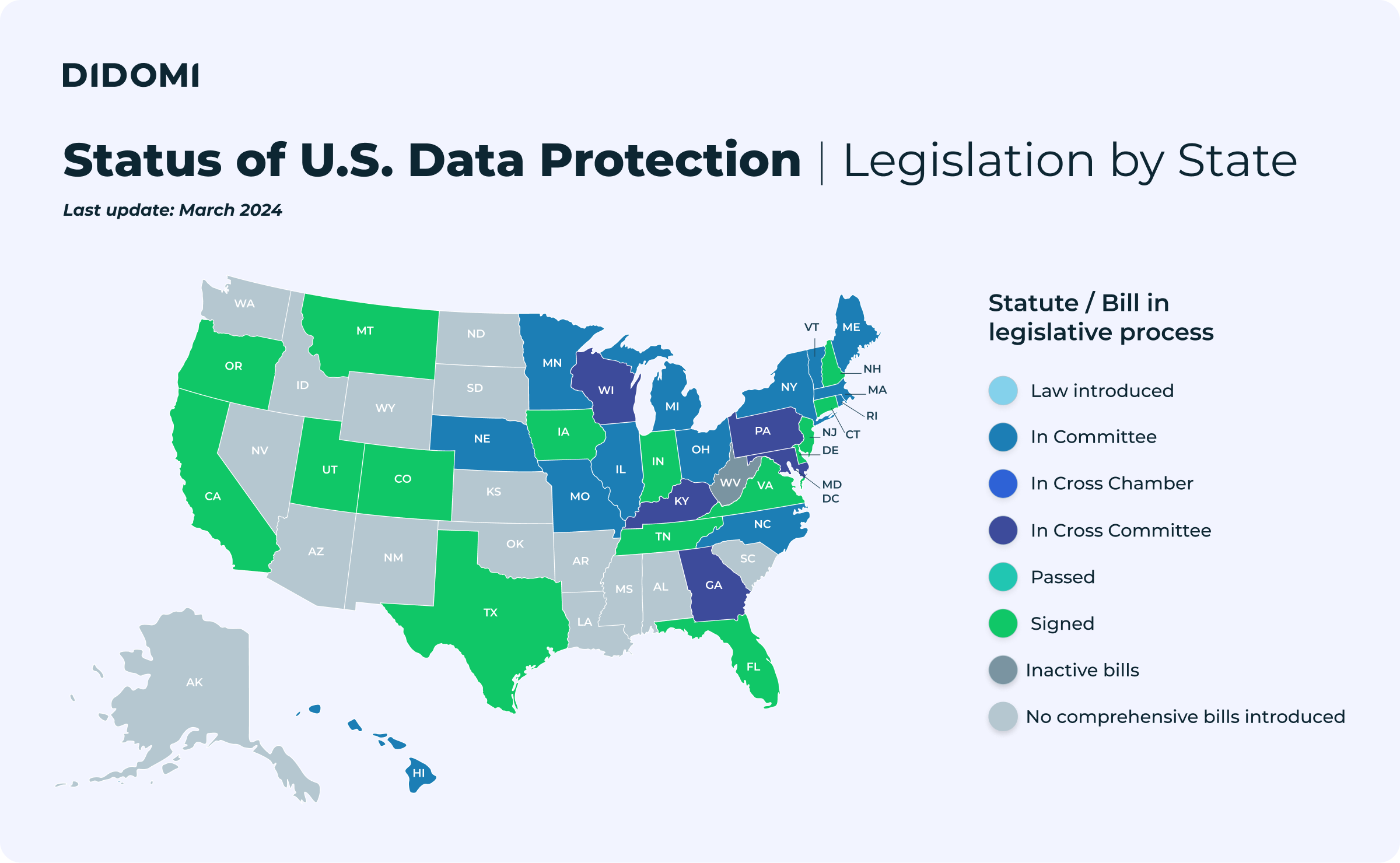

Note: Before reading the full article, grab your privacy legislation tracker cheatsheet, last updated in March 2024:

You can download a PDF version here. For a map version, scroll down to check our U.S. State Legislation Map. |

Summary

A brief history of U.S. privacy laws

The concept of privacy rights is not exactly new. As far back as 1890, writing in the Harvard Law Review, future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis and his law partner published “The Right to Privacy,” considered the first major article to make the case for a legal right to privacy.

In it, they wrote that:

|

"Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual … the right ‘to be let alone’ … Numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops." |

Nearly thirty years later, in the context of telephone technology, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of wiretapping in Olmstead v. United States, a case involving government wiretaps of a suspected bootlegger. But Brandeis dissented, arguing for a Constitutional privacy right in the Fourth Amendment, which protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government.

“The progress of science in furnishing the Government with means of espionage is not likely to stop with wiretapping,” wrote Brandeis in Olmstead. “Ways may someday be developed by which the Government, without removing papers from secret drawers, can reproduce them in court, and by which it will be enabled to expose to a jury the most intimate occurrences of the home.”

Prophetic as he was, neither Brandeis, writing in 1928, nor the framers of the U.S. constitution, writing in 1787, could have foreseen the internet technology that has sparked today’s data privacy concerns. They also failed to anticipate that private companies would one day wield powers rivaling those of governments.

However, Brandeis did accurately anticipate the conflict between technology, privacy, and the law. The law is continually playing catch up with rapidly-changing technologies. This is a problem in every country, not just the United States. But in the U.S., a slow-moving legislature is a feature, not a bug.

The framers viewed a slow and difficult legislative process as a check on federal power, making it more difficult for the government to infringe on the liberties and rights of citizens. Restricting power at the federal level gave individual states a great deal of authority. So while privacy rights and technology were not, and could not have been, explicitly addressed by the framers, this federalist dynamic helps to explain why states have been quicker to enact sweeping privacy laws than Congress.

Existing federal data privacy laws in the U.S.

Data, as we understand it today, entered the lexicon in the 1940s, shortly after the invention of ENIAC, generally regarded as the first modern computer. "Data-processing", "database", and "data entry" followed soon thereafter.

The U.S. Privacy Act of 1974

Computer databases, used by the federal government to hold data on private citizens, led to the nation’s first data privacy law—the U.S. Privacy Act of 1974.

Many of the privacy issues addressed by the Privacy Act echo what we’re still debating today. Namely, people were concerned about the government potentially abusing its vast computer databases of individuals’ personal data. Thus, Congress enacted legislation that encoded a number of citizen rights pertaining to data held by U.S. government agencies, including:

-

Public notice requirements about the existence of databases

-

Individual access to records

-

The right of an individual to make copies of their records

-

The right of an individual to correct an incomplete or erroneous record

-

Restrictions on the disclosure of data

-

Data minimization requirements

-

Limits on data sharing

-

Penalties for violating the Privacy Act

The Privacy Act balanced the need of the government to maintain information about citizens with the rights of citizens to be protected against unwarranted privacy invasions resulting from federal agencies’ collection, maintenance, use, and disclosure of their personal information. This early privacy law laid out many provisions in modern privacy legislation.

Unfortunately, because the law applies only to federal agencies, the Privacy Act is not up to the task of protecting data privacy rights in a world where the private sector collects more data than any government agency. The law also could not have foreseen the vast types of data now collected about us—everything from our location and browsing activity to our biometric and genetic data.

Other U.S. privacy laws

Additional data privacy legislation has been passed since the Privacy Act. And while these laws expand on the 1974 law, they generally only restrict limited data types and the specific entities that handle them.

-

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) regulates health information privacy rights. Individuals have the rights to access the personal information in their health records, ask to change wrong, missing, or incomplete information, know who the information is shared with, and limit sharing of it. HIPAA covers health care providers, hospitals and clinics, insurers, and certain third party businesses, like pharmacies. It does not cover health care apps and wearable devices like Fitbit.

-

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), enacted in 1999, is primarily a piece of financial services reform legislation. Buried within it, though, are rules that address consumer financial privacy. The GLBA requires financial institutions to disclose to customers, in a “clear and conspicuous” privacy notice, the types of “nonpublic personal information" (NPI) it collects about them, how it’s used, and who it’s shared with. They must also provide an opt-out mechanism to customers who don’t want their information shared with unaffiliated companies. Therein lies a major loophole: among affiliates in the same “corporate family,” customer NPI rights don’t apply.

-

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) of 1970 predates the Privacy Act and deals with the personal information contained in consumer credit reports. Under the FCRA, consumers have the right to know what information is in their credit file, dispute any errors in it, and whether it has been used against them in an “adverse action” (such as being denied employment). Entities that compile credit reports, send information contained in credit reports, and use credit reports are subject to the FCRA.

-

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) regulates personal information collected from children younger than thirteen. It imposes requirements on commercial websites and online service providers that collect, disclose, or use personal information from twelve and under. COPPA compliance is enforced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Violations can result in a fine. Several social media and tech companies have violated the COPPA, including TikTok ($5.7 million fine) and YouTube ($170 million fine).

In addition to these laws, a smattering of other privacy laws regulate personal information gathered by the telecommunications industry, including the Telephone Records and Privacy Protection Act (TRPPA), the Cable Communications Policy Act, the Communications Act, and the Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA).

But each of these laws has major shortcomings. For example, the Communications Act and the TRPPA require phone companies to play nice with phone records, but they do nothing to protect the data of smartphone users accessing the internet. The VPPA protects VHS rental records, but doesn’t apply to video streaming companies. And with fewer and fewer people subscribing to cable services, cable TV data is increasingly irrelevant.

The FTC and privacy policy enforcement actions

Want further proof that our existing data privacy laws are not up to snuff in the internet age? The FTC, the agency that enforces the COPPA, the GLBA, and the FCRA has the authority to impose civil penalties on companies for “deceptive practices or acts.” The FTC did just that against Facebook in 2011, and again in 2019 due to false claims that Facebook made over its data privacy policy. The latter instance resulted in a record $5 billion fine.

But here’s the catch: the FTC was only able to hold Facebook accountable for its privacy policy because Facebook did not live up to the promises it made in that policy. If Facebook had not implemented a privacy policy in the first place, the FTC would have had no grounds to bring a complaint against the company for its “deceptive practices or acts.”

In other words, from an FTC enforcement perspective, a business has to adhere to the terms of their posted privacy only if they have one. If they don’t have one, they don’t have to adhere to it.

The FTC, though, is on track to pick up some of the slack left by failed Congressional efforts to pass a federal privacy law. FTC Chair Linda Khan has publicly stated that the agency intends to use its authority to regulate data privacy and security purposes. The FTC did just that in 2022, bringing suit against Kochava, Inc. for its sale of customers’ sensitive geolocation data, securing two record-breaking settlement agreements with Epic Games, Inc. for collecting children’s personal information without parental consent and entering into a consent agreement with Drizly, LLC for inadequate cybersecurity practices that allegedly resulted in a data breach.

More enforcement powers could be handed to the FTC as a result of the agency’s “commercial surveillance and data security” rulemaking, launched in August 2022. The rulemaking process could end with new FTC regulations that cover the collection, use, and sale of data, cyberattacks and data theft, dark patterns, how data practices affect vulnerable populations, biometrics, consumer consent, and much more.

Law firm Kelley Drye & Warren says the proposed rulemaking is “remarkably sweeping in scope” and raises issues “that are clearly beyond the FTC’s authority.” FTC rulemaking typically takes years to finalize, and there is no guarantee that this current effort will end with an enforceable rule.

But with general privacy legislation stalled in Congress, the FTC could push aggressively to craft impactful data privacy regulation.

Self-regulation and online advertising

The FTC’s growing interest in online data collection practices, sparked by the emergence of e-commerce in the 1990s, was addressed in a 2009 report, “Self-Regulatory Principles for Online Behavioral Advertising.”

In that report, the FTC described the ubiquitous practice of websites using cookies to track an online user’s browsing activity and deliver their ads tailored to their interests. Cookies (text files containing data) are what allow advertisers to follow users around the internet and serve custom ads based on their web browsing history. The FTC noted that tracking online activities for personalized advertising—a practice known as online behavioral advertising or interest-based advertising—raises concerns about consumer privacy.

Responding to these privacy concerns, the FTC proposed self-regulatory principles in its report. Self-regulation was favored because it provides the flexibility needed to address “evolving online business models.” The FTC’s proposed principles informed the Self-Regulatory Program for Online Behavioral Advertising, an initiative of the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA).

The DAA initiative, introduced in 2009, applies seven principles to online behavioral advertising that cover:

-

Education

-

Transparency

-

Consumer control

-

Data security

-

Material changes

-

Sensitive data

-

Accountability

Consumers will be familiar with the YourAdChoices Icon. Web pages that display the Icon on or near advertisements are covered by the self-regulatory program. Clicking on the icon takes consumers to a disclosure statement about data collection and use practices associated with the advertisement. They can also opt out of these practices and learn more about the company behind the ad.

Hundreds of companies participate in the DAA’s YourAdChoices program. It has an enforcement mechanism administered by DAA member organizations, the Council of Better Business Bureaus (CBBB), and the Association of National Advertisers (ANA). Consumer complaints (such as a broken opt-out link) can be made with the BBB and the ANA.

Companies that don’t cooperate with efforts to resolve a reported issue can be named publicly and referred to a federal or state law enforcement authority for further review. However, referrals are rare; there have only been a handful in the history of the DAA program. Noncompliance with DAA self-regulatory principles could qualify as a deceptive practice under consumer protection and false advertising laws, leading to potential fines or penalties.

A federal data privacy law could be on the horizon

Some have called for an expansion of FTC rule-making authority to rein in data abuses. Based on recent FTC activity, things could be moving that way.

Others insist that a broad federal law—a U.S. GDPR equivalent—is needed. Such a law would require companies to post a privacy policy and adhere to the terms, and it might resemble what’s proposed here.

There is general consensus around the need for federal data privacy legislation, especially as the patchwork of state laws grows and federal efforts to pass privacy legislation are ongoing. According to the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP), dozens of privacy-related bills have made their way through Congress. The IAPP expresses optimism that a U.S. federal privacy law is in the nation’s future.

During the 117th Congress, several pieces of privacy legislation were introduced in both the House and the Senate, while there were a handful of House privacy bills and around a dozen Senate bills. Not all of these were related strictly to consumer data, but at least one—the Consumer Data Privacy and Security Act—sought to establish uniform federal standards for data privacy protection. A press release for the bill, sponsored by Jerry Moran of Kansas, cited survey results showing that 83% of Americans believe data privacy legislation should be a top priority for Congress.

Similar legislation was introduced in 2021 by a bipartisan coalition of Senators from Minnesota, Louisiana, West Virginia, and North Carolina. A narrower piece of data privacy legislation, the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act, would radically reshape online advertising by banning the use of personal data for targeted advertising, including protected class information (e.g., gender, race, and religion) and information purchased from data brokers.

The American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) gained enough bipartisan support in 2022 to garner real enthusiasm that a federal privacy law could finally be passed. However, the bill never made it to the House floor for a full vote and ultimately went the way of its predecessors.

There have been calls to reintroduce the ADPPA during the 2023 session of Congress. In a January 2023 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, President Biden challenged Congress to pass legislation that provides “serious federal protection for Americans’ privacy”—an apparent nod to the ADPPA.

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Subcommittee on Innovation, Data and Commerce held a March 2023 hearing on the ADPPA. While the hearing seemed to confirm that bipartisan support for the bill remains, and no competing privacy framework is being considered at this time, federal preemption remains a major sticking point in ADPPA talks, especially as more states pass and propose privacy legislation.

U.S. state data protection laws

The path forward for a national privacy law remains unclear. But as federal privacy legislation remains bogged down in Congress, on the state level, privacy laws are being passed at a rapid pace.

At the time of the ADPPA hearing in March, at least twenty states were considering some type of comprehensive privacy bill on top of the state data privacy laws that have already been passed.

In 2023 alone, five states—Iowa, Indiana, Montana, Tennessee, and Texas —signed privacy bills into law. One additional state—Oregon—has passed a privacy law, making it the eleventh state to do so. And as of July 2023, three more states—Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania—have active bills.

To put this rapid rate of privacy law adoption into perspective, in 2018, the year that California passed the first statewide consumer privacy law, just one other state (New Jersey) introduced a privacy bill. In 2021, twenty-nine bills were introduced in twenty-three states. Two of those states—Colorado and Virginia—joined California in enacting privacy legislation.

In 2022, 29 states and the District of Columbia introduced a data privacy bill or carried a bill over from the previous year’s legislative session. In total, 60 privacy bills were considered. However, despite this flurry of legislative activity, just two states—Connecticut and Utah—passed privacy laws in 2022.

However, 2023 is shaping to be the year the dam breaks on state privacy legislation.

States like Utah and Iowa showed that new bills can be introduced and passed very quickly when there is political alignment on the data privacy issue. Republican-controlled Iowa, Indiana, Montana, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah also show that data privacy is not a red-state issue or a blue-state issue. It’s an issue important to all Americans.

Jan Schakowsky, Ranking Member of the Subcommittee on Innovation, Data and Commerce, said at a recent ADPPA hearing:

|

"We heard the cry of the vast majority of Americans who are really tired of feeling helpless online…I think it's time for us to roll up our sleeves and in a bipartisan way.”

- Jan Schakowsky , United States Representative (source: IAPP) |

Yet the longer the U.S. goes without a federal privacy law, and the more states take privacy matters into their own hands, the more complicated the preemption question becomes. A 10-state coalition of attorneys general led by California last year sent a letter to Congress expressing their opposition to preemption provisions in the ADPPA. California doubled down on its opposition in a more recent February 2023 statement.

Given the trends of Congressional fiddling and state action, businesses realistically face the prospect of a 50-state privacy regime in the not-too-distant future.

-

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) cemented California as one of the top states for consumer protection by extending consumer rights to the personal data sphere. Ironically, California Democrats could be an obstacle to nationwide legislation if a privacy bill does not offer protections that are at least equal to those in California. Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other California officials were credited with shelving the ADPPA on these grounds.

-

The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), which takes effect January 1, 2023 and amends the CCPA, is California’s second legislative foray into data privacy. It gives Californians new data rights, changes the criteria for covered businesses, and introduces data minimization principles, and creates a new state regulatory agency. A recent California court order has delayed CPRA enforcement until March 29, 2024.

-

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) enhances consumer privacy protection by giving Colorado residents five major rights and imposing duties on covered entities. Based in large part on the failed Washington Privacy Act, it adopts the controller-processor approach found in the EU’s GDPR. The law went into effect July 1, 2023.

-

The Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA) made Connecticut the fifth state to adopt data privacy legislation. While the CTDPA takes many of its cues from similar state laws, most notably the CPA, it also has a few unique provisions, such as not requiring consumer opt-outs to be authenticated. The CTDPA took effect on July 1, 2023.

-

The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) was the second broad data privacy bill to win state approval. The VCDPA, a middle ground between pro-consumer and pro-business interests, moved quickly through the legislature and passed by a large margin. The law became effective January 1, 2023.

-

The Utah Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA) is seen by privacy experts as more business-friendly than comparable state laws. As the first “red” state to pass a law of this kind, Utah shows that data privacy is a bipartisan issue. The UCPA approved by the state legislature in just 5 working days, goes into effect December 23, 2022.

-

Iowa SF 262 was signed into law on March 29, 2023, making Iowa the sixth state to pass comprehensive privacy legislation. It takes a similar approach to other state privacy laws and has been compared most closely to Utah’s for its business-friendly provisions. The law will go into effect on January 1, 2025.

-

The Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act (ICDPA) was enacted on May 1, 2023. The transparency and disclosure obligations that the Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act places on covered entities are similar to those in Colorado, Connecticut, and Virginia, but Indiana is giving companies a 2.5-year runway to prepare for a January 1, 2026 effective date.

-

The Tennessee Information Protection Act (TIPA) was the third state data privacy law in six weeks—and the 8th overall—to gain a governor’s signature after it passed unanimously through both houses of the state legislature. Like Iowa, Utah, and Virginia laws, the TIPA takes a more business-friendly approach. It goes into effect July 1, 2025.

-

The Montana Consumer Privacy Act (MCDPA) joined the ranks of state privacy law on May 19, 2023. Scheduled to take effect on October 1, 2024, the MCDPA closely resembles the Connecticut Data Privacy Act in several key aspects, including permitting consumers to opt out of the processing or sale of personal data for targeted advertisements.

-

The Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPSA) made Texas the tenth state to pass a data privacy bill and the fifth to enact or pass one in a seven-week span. Passed on May 29 and signed by Governor Abbott on June 18, the Texas law borrows from Virginia’s but throws in a few twists, such as a unique three-factor coverage threshold standard. The TDPSA will take effect on July 1, 2024.

-

The Oregon Consumer Privacy Act (OCPA) was the eleventh U.S. legislation (the sixth in 2023) to pass. Husch Blackwell calls it “one of the strongest” laws passed so far. Senate Bill 619 is largely similar to laws in other states but is noteworthy for not providing a broad exemption to non-profits or entities regulated by HIPAA. Once signed into law, the OCPA will take effect on July 1, 2024.

Common data privacy principles

Many privacy bills die in committee or are voted down. However, a comparison of the proposed bills gives insight into the common privacy provisions that lawmakers are thinking about. A lot of them harken back to privacy concepts introduced in the 1974 Privacy Act and expanded in subsequent American privacy laws. But there are concepts more specific to the internet, too.

-

Right of access: Consumers have the right to access the data a business collects about them and to access the data that is shared with third parties.

-

Right of rectification: Consumers have the right to request the correction of incorrect or outdated personal data.

-

Right of deletion: Consumers have the right to request the deletion of their personal data.

-

Right of restriction of processing: Consumers have the right to restrict the ability of businesses to process their data.

-

Right of portability: Consumers have the right to request the disclosure of their data in a common file format.

-

Right of opt-out: Consumers have the right to opt-out of the sale of their data to third parties.

-

Private right of action: Consumers have the right to file a lawsuit for civil damages against a business that violates a privacy law.

The IAPP lists ten more of these privacy provisions that are typically found in legislative proposals. Aside from creating consumer rights, the bills that have been introduced impose obligations on businesses. These obligations include:

-

Data breach notifications: Businesses must notify consumers about privacy or security breaches.

-

Notice requirements: Businesses must give notices to consumers related to data practices and privacy policies.

-

Discrimination prohibitions: Businesses may not discriminate against consumers who exercise their data privacy rights.

-

Data minimization policies: Businesses should only collect and/or process the minimum amount of data required for a specific purpose.

It can be helpful to look at the common provisions in state privacy laws that are passed to gauge where legislators are finding common ground—and where privacy programs should be focused.

For example, all privacy laws passed to date grant the right to access, the right to delete, the right to portability, and the right to opt-out of data sales. All states also impose notice/transparency requirements on businesses, and no state allows prohibitions on discrimination for exercising data privacy rights. Only Iowa does not require risk assessments and only Utah does not impose a GDPR-style purpose/processing limitation.

Sticking points in state data privacy laws

No state has legislation—passed or proposed—that ticks every box in the privacy provision checklist. But two provisions have emerged as major sticking points in getting privacy laws passed: a private right to action and an opt-in consent policy. Both are seen by privacy experts as more consumer-friendly.

-

A private right to action means that a consumer can take civil legal action against a business that violates a data privacy law. Because most privacy violations aren’t isolated incidents, and affect many consumers in the same way, the private right to action often takes the form of a class action lawsuit, as is seen with data breach litigation.

Of the data privacy laws passed to date, only California has a private right to action. However, it is limited to data breaches, although CPRA draft regulations are set to expand the definition of what constitutes a breach. Legislation has failed in several states over lawmaker disagreements on a private right to action.

-

Opt-in consent refers to the idea that regulated entities must obtain consumer consent in order to collect, share, or sell private information to third parties. Essentially, opt-in consent shifts the consent burden from the consumer to the regulated entity, compared to opt-out consent, which places the burden on the consumer.

A strictly opt-in approach–like that found in Europe’s GDPR–favors consumers but is rare in the U.S., except in the cases of children, young teenagers, and in some states, a category of data known as “sensitive data.”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Like other laws, data privacy laws are page after page of confounding legal language that can make it difficult to understand what, exactly, the statute allows and prohibits.

Companies that are subject to state privacy laws should consult with a local data privacy attorney to ensure compliance. In general, measures to comply in states with active laws should be sufficient to ensure compliance in other states that adopt privacy legislation. But a peak under the hood of these laws reveals how each poses slightly different challenges for affected companies.

Who does the law apply to?

This point is pretty straightforward. A state-level privacy law only applies to residents of that state. The CCPA only applies to California residents, the CPA to Colorado residents, the VCDPA to Virginia residents, and so on.

A consumer doesn’t necessarily have to be physically present in the state, but they must be a state resident.

What is considered covered personal information?

Here, there is considerable variance from state to state.

-

The CCPA defines personal information as “information that identifies, relates to, or could reasonably be linked with you or your household.” California has also introduced the concept of “probabilistic identifiers.” The CPRA amends the CCPA definition of personal information by introducing “sensitive personal information” as a new category of PI.

-

The VCDPA defines personal data as “information linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable individual” (and not a household or device), with the exception of de-identified and publicly available data.

-

The CPA definition of covered personal information is virtually identical to Virginia’s, but with a less restrictive definition of “publicly available information.”

-

The CTDPA uses the familiar criteria of information that is “linked or reasonably linkable” to an individual, with the usual exclusions for deidentified data or public information.

-

The UCPA adds the term “aggregated” data to the categories of deidentified and publicly available data excluded from protections. It also has a definition of “sensitive” data.

-

Iowa SF 262 refers to “personal data” and takes the same tack as Virginia, Colorado, and Connecticut, making exemptions for de-identified or aggregate data or publicly available information. It includes a “sensitive data” category as well that covers categories like race, religion, genetic data, biometric data, children’s personal data, and “precise geolocation data” (within 1,750 ft.)

-

Indiana’s law requires additional consumer consent to process “sensitive personal information,” a category that, like Iowa, has a geolocation data category.

-

Tennessee’s law has a long list of what qualifies as “personal information.” Notably, it considers an “alias” to be an identifier and financial, medical, and health insurance information to be identifying personal information. Also in the TN personal information category are commercial information, protected legal classifications, biometric data, geolocation data, employment data, and even “olfactory” and “thermal” information.

-

Montana SB 384 uses the term “personal data” instead of “personal information” in its definitions section.

-

Texas’ TDPSA includes pseudonymous as a type of “personal data” when such data can be used with other information to link it to an individual. Texas also recognizes the category of “sensitive data.”

-

Oregon has a more inclusive definition of “sensitive data” than other states that includes a person’s status as a crime victim or somebody of transgender or nonbinary status.

What is a “controller” or “processor”?

“Controllers” and “processors” are terms lifted from the European GDPR. In the United States, the terms have near-identical meanings, but there are subtle variations in statutory language.

For example, under Virginia law, a controller is a “natural or legal entity that, alone or jointly with others, determines the purpose and means of processing personal data.” A processor in Virginia is an entity that processes data on behalf of a controller.

Colorado and Iowa use these same terms in their laws, but in defining them refer to a “person” rather than a “natural or legal entity.” Legally, the terms mean the same thing. Yet the different wordings show how legalese, without intending to, can make parsing these statutes something of a head-spinning experience.

To further illustrate this point, California foregoes the language of “controller” and “processor” altogether, opting instead to use the terms “businesses” and “service providers.” These might seem like minor differences, but the CCPA/CPRA has narrow definitions for “business” and “service provider.”

The devil is in the details.

Are there exemptions?

Exemptions exist at a few levels in state data privacy laws. Consumer activity outside of the state where the regulation applies is generally exempted. So is data specifically governed by other laws, including HIPAA, the GLBA, and state laws like the California Financial Information Privacy Act (CalFIPA).

The CPA and the OCPA do not have a HIPAA exemption. Connecticut and Oregon also do not exempt nonprofits from complying with the law. Iowa has a non-profit exemption, too.

Employment data is exempt in all states except for California, where the CPRA gives privacy protection rights to employees of covered businesses. Finally, the laws apply to private entities—not to government agencies or public institutions like institutions of higher education.

What are the penalties for violating state data protection laws?

State enforcement authorities generally give businesses that violate their state’s data protection law a period of time, known as a “cure period,” to come into compliance. Failure to cure a violation subjects a company to further enforcement measures at the hands of state authorities. Some states have cure period provisions that expire on a certain date.

-

In California, companies that violate the CCPA can receive a civil penalty of $2,500 per unintentional violation and $7,500 per intentional violation. The CCPA is unique in providing a private right of action to individual consumers. California consumers that are the victim of a data breach can sue businesses, as an individual or as a class, for $150 to $750 per individual.

Businesses accused of a data breach may cure the alleged violation within 30 days to avoid paying statutory damages, although early case law has not definitively interpreted which unauthorized data disclosures can be cured and how. Under the CPRA, primary enforcement authority will shift from the AG to the newly-created California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA). The CPRA also eliminates the CCPA’s 30-day cure period. -

CTDPA violations are treated as an unfair trade practice and subject to civil penalties up to $5,000 per violation. The Connecticut Attorney General also has discretionary power to impose remedies that include disgorgement, injunctive relief, and restitution.

-

Colorado considers a violation of the CPA to be a deceptive trade practice, with civil penalties up to $20,000 per violation. Each consumer affected may constitute a separate violation, but the maximum penalty is $500,000 for a series of related violations. The CPA’s 60-day cure period is set to expire January 1, 2025. At that time, enforcement actions may be initiated without a notice period.

-

Utah has a unique two-tiered enforcement scheme. Consumer complaints start with the state’s Division of Consumer Protection, which then has the option to pass the complaint on to the AG for possible action. UCPA violations not cured within 30 days are subject to fines up to $7,500. The money that the Utah AG receives from enforcement actions will be deposited into the Consumer Privacy Account to fund UCPA education and enforcement efforts.

-

Virginia companies found to be in violation of the VCDPA will be subject to a civil penalty of up to $7,500 per violation. Companies may also be subject to an injunction (i.e., a judicial order) to restrain further violations of the VCDPA. The Virginia Attorney General may recover attorneys’ fees and other expenses incurred while investigating and preparing an enforcement action under the VCDPA.

-

In Iowa, businesses that remain in violation of SF 262 after the 90-day cure period can face an injunction and civil penalties of up to $7,500 per violation, to be paid into the state’s consumer education and litigation fund.

-

The Indiana Data Privacy law has a non-sunsetting 30-day cure period for alleged violations, after which a controller or processor could be subject to an injunction and civil penalties of up to $7,500 per uncured violation.

-

The Tennessee Information Protection Act has a 60-day cure period. TN’s AG can impose civil penalties of up to $7,500 per privacy breach, plus attorneys’ fees and investigative costs. Companies accused of breaking the law can assert an affirmative defense if they have a written privacy program that meets NIST Privacy Framework requirements.

-

Montana has a 60-day cure period, but this provision sunsets on April 1, 2026. Unlike other state privacy laws, the MCDPA does not specify available remedies or place limits on the monetary penalties the AG may seek to enforce the law.

-

The consequences for not complying with Texas’ data privacy law are up to $7,500 per violation, but the TDPSA has a 30-day cure window that does not sunset.

-

Oregon’s OCPA provides the standard 30-day cure period (with a sunset date of January 1, 2026) and $7,500 maximum fine per violation. OCPA enforcement actions are subject to a five-year statute of limitations.

What is the difference between the CCPA and the CPRA?

The CPRA amends and replaces several parts of the CCPA. Notable changes include:

-

Threshold requirements for businesses that must comply

-

Addition of a new protected data category

-

New consumer rights

-

Creation of a new enforcement agency, the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA)

-

Adoption of a GDPR-style data minimization requirement

-

Expansion of personal information categories that give consumers the right to take data breach legal action

-

Required annual cybersecurity audits for data processing firms

Notably, enforcement risks are expected to increase under the CPRA not only due to new consumer rights and new obligations placed on covered businesses but also due to the CPPA and California’s new regulatory scheme. The CPPA is the first agency in the country dedicated to consumer privacy issues. It has the authority to investigate potential CPRA violations–on the basis of a sworn individual complaint or on its own initiative–and to take administrative action to enforce violations.

While it shares enforcement authority with the California AG, which can seek penalties through civil action, the CPPA is expected to take the lead in enforcing the CPRA. The agency will have a budget that is more than twice as large as the budget the California AG office currently has for CCPA investigation and enforcement, allowing it to hire more staff and engage in closer scrutiny of businesses. In addition, CPRA monetary recoveries will be deposited into a fund that in the future will provide most of the CPPA’s funding.

In short, when enforcement of the CPRA begins on March 29, 2024, in addition to the resources the AG’s office can deploy toward alleged noncompliance, the CPPA will be empowered–and incentivized–to engage in regulatory oversight, which has all the makings of a much more vigorous enforcement environment.

The growing patchwork of state privacy laws is a challenge for smaller businesses

More states passing data protection laws is good news for consumers and further evidence that the data privacy revolution is well underway. But growing layers of state regulations pose a greater legal challenge for small and medium-sized businesses, which, unlike big companies, often lack the in-house resources to adjust their compliance strategies jurisdiction by jurisdiction.

Businesses still have time to get their compliance checklist in order ahead of state laws taking effect later in 2023. Companies subject to multiple state privacy laws should focus on developing privacy programs that satisfy common requirements.

To learn how Didomi can help, schedule a call with one of our experts: